Thomas van den Bliek, 2/5, home blogger ArtEZ Business Centre

Product Design

Loneliness

We’re increasingly connected to each other. Technology allows me to make friends across the world without having met them even once. But what kind of relationship is built through the mediation of technology? And doesn’t it get more difficult to maintain contact when you’re expected to reply to everyone?

Loneliness is a feeling of disconnection. You experience a lack of close emotional ties to others. Or you have fewer social contacts than you’d like. Loneliness is characterized by negative emotions of emptiness, sadness, anxiety and a sense of meaninglessness, as well as a range of physical and psychological complaints.

In a study for the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment in 2016, 44% of the adult population (19+) in the Netherlands described themselves as ‘lonely’. One in ten of the surveyed identified with feelings of severe loneliness. Loneliness is not the same as solitude, although they can coincide. When somebody has no or very few social contacts, we speak of social isolation.

Briefing Transition program 2019 by Frank Kolkman

Money also plays a role: loneliness is less common among people with a higher income than among low-income people. The rate of severe loneliness for people who have difficulty making ends meet is 17%; for those who have no difficulty getting by, it is 6%.

The Transition research program has taken these figures as a starting point for design proposals which engage with, and potentially have an impact on, loneliness. Under the direction of Frank Kolkman, third-year students of Product Design and Interaction Design engaged in a collaborative effort to research loneliness and to propose products, services, interfaces or strategies that can expose and address loneliness.

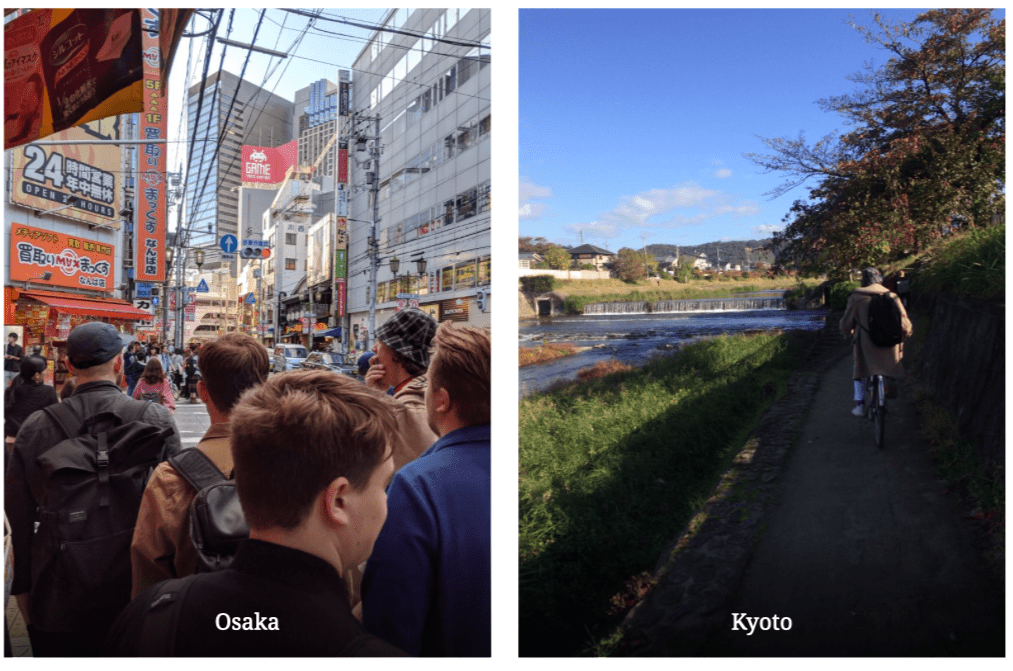

A part of the Transition program this year was a research field trip to Kyoto, Japan, for a three-day workshop at the Kyoto Institute of Technology (KIT) combined with studio visits and sightseeing in the cities of Kyoto and Osaka. Together with 8 students, teacher Frank Kolkman and fellow alum Mireille Steinhage, I departed to Japan on the 2nd of November.

Osaka

On our first day we visit Osaka: a city with approximately 2.7 million inhabitants. Osaka is one of Japan’s most important industrial centers and the isolation that people live in is immediately apparent to us. In one of the many arcade halls, all we hear is the sound of the gaming machines. You don’t hear people chatting or laughing. When I enter, I encounter people completely absorbed in their screens, focused exclusively on achieving a high score. In a corner on my right, a man in a suit is dancing exuberantly to Dance Dance Revolution. For a moment, his attention is far removed from his heavy workload and he has completely surrendered to the dance battle.

One floor up, we encounter young people my age facing pink machines. There are folders filled with cards enabling them to unlock accessories and clothing for their digital girlfriends on the screens in front of them. A completely bizarre scenario to my eyes, but a normal everyday activity to them. Taking – or maintaining – a boyfriend or girlfriend can be done digitally but is also provided as a service you can purchase on the streets. There are various opportunities to hire a boyfriend. These guys, styled like pop stars, can help you stay entertained throughout the day.

Keep in touch

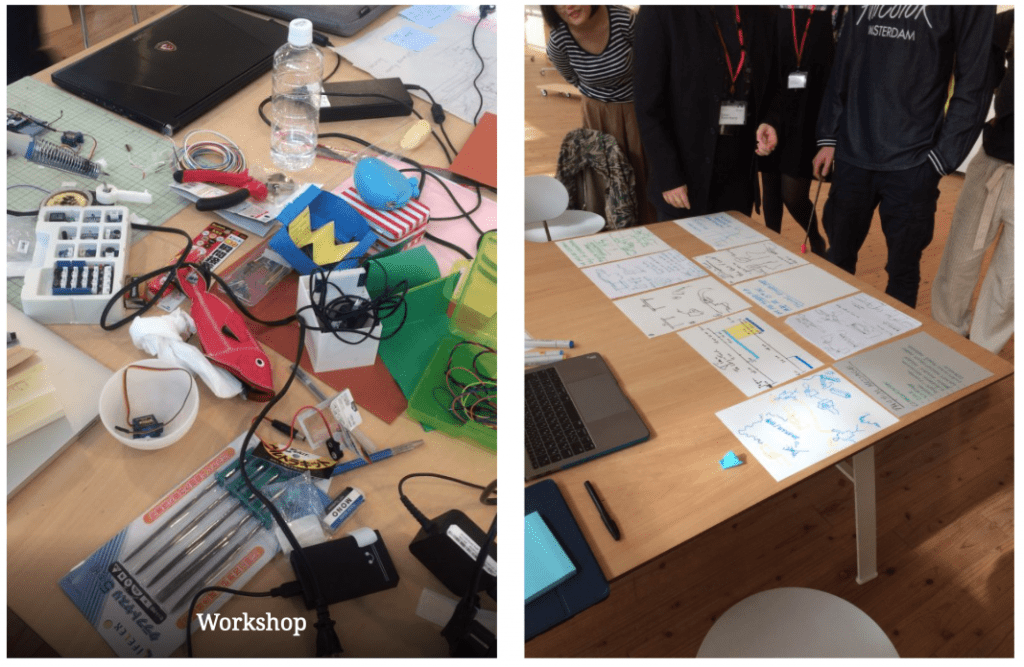

Compared to Osaka, Kyoto is a tranquil and peaceful city. Whereas Osaka overwhelmed me with its neon lights and lavish shops, in Kyoto I find myself quietly cycling by the river towards the university. In the Kyoto Design Lab, several teams of ArtEZ and KIT students worked together in a three-day workshop with the theme “Keep in touch.” The research question was very clear: how can we maintain contact with one another while avoiding superficiality? There are various challenges here, like the eight-hour time zone difference and the fact that we only spent four days together. Can we use this to our advantage, or does it complicate the effort to keep in touch?

In the end, this dynamic workshop led to interesting prototypes. Proposals included capturing sounds and sending them to each other; a finger trap, which one person in the group should always be wearing, requiring daily negotiations and arrangements to decide who’ll be wearing it on which day; using the time difference to create human alarm clocks, allowing us to wake each other up in time; an open-source design challenge where the team works together on various designs at a distance; and finally four lamps that are connected to each other. If someone switches the lamp off in the Netherlands, it will also switch off in Japan.

The research fieldtrip was also combined with a number of studio and company visits. At Panasonic we had a peek at the products made by the Electronics meet Crafts research team: artisanal, traditional crafting combined with new technology.

At the ATR (Advanced Telecommunications Research Institute International) we see another approach to coping with loneliness. The Japanese engineer Hiroshi Ishiguro made a robot clone of himself, which became his identity: a geminoid who has taken over for his creator. To keep looking like his doppelganger, Ishiguro periodically undergoes cosmetic surgery. He built the robot to explore what it’s like to be human. His girlfriend, too, was duplicated in a replica that needs neither food nor rest, but which is always ‘on’ and ready for a chat.

Other than these humanoid robots, we look at various communication robots. These physical robots are integrated with telecommunications systems, giving people an intimate way to stay in touch with each other over long distances..

In American films, robots are almost always evil – they are created by humans but intend to kill their creators. In Japan, on the other hand, robots play heroic roles. For me, the friction results from our desire to create robots that understand us. We want user-friendly technology that resembles humans, but at the same time we fear that resemblance. I experienced an inhuman, uncanny feeling when I shook the hand of the geminoid and it asked me how I was doing. Is this the future we want? A future where robots are indistinguishable from humans? In Japanese culture, it’s more important that we envision our ways of living together with robots and the roles they will play in our lives.

Cash

In the research for my graduation collection Objects for a Cashless Society, I explore how the digitalization of money results in the loss of small social contacts. In the Netherlands, as in many Western countries, a variety of new systems is being developed to make payments frictionless and faster. In the highly technological Japan, however, I find that cash is not yet on its way out. After two days, my wallet is bulging with 1-yen coins (0,0082 euro). I expected even the simplest payments to be digital, and yet I end up paying in cash at the supermarket for my lunch. The ATMs, on the other hand, are equipped with huge physical buttons and make science fiction noises when you press them. No shortage of vending machines in Japan, generally. From useless trinkets to warm cans of coffee. Whatever it is, Japan will have a vending machine for it.

Money in Japan is linked to different rituals than in the Netherlands. Tipping is uncommon, or even offensive. Let alone bargaining over prices: this is considered extremely inappropriate.

But can systems of payment – or the emotional value of money – lead to more human connection? As I described, small social aspects of trade are eroding through the digitalization of money. Technology speeds up our transactions, leaving less time for a short chat.

Innovation results in changes to certain systems. But what are the consequences of new innovations? What are the side effects that only become visible in the long run? For me, innovation means progress, but we also need to consider the human aspect and the consequences it might have on our everyday life. Maybe, like Hiroshi Ishiguro, we need to construct a mirror that tells us what it means to be human, in order to generate a desirable future.

Translation by: Witold van Ratingen

Thomas van den Bliek

I’m a product designer with an interest in new technologies. My fascination for the transition from an analog to a digital world has led me to explore the byproducts that emerge with these new technologies and systems. I want to question the frictionless life that the digital era promotes and recover the human aspect through design propositions.