Fadia Ba’abduh channels her experiences of war and loss through her work: “We must accept death”

- Architecture and...

At 20, Fadia fled violence in her home country Yemen. Fadia Ba’abduh came to the Netherlands seeking asylum and spent the first years of her new life learning the language and studying. She also became a mother and enrolled in the master Architecture at ArtEZ Academy of Architecture in Arnhem, which she finished in 2024. Her graduation research, Moment van Herinnering (“Moments of Remembrance”), is especially where Fadia makes a big impression. “After the loss of my parents, I am no longer fearful or woeful about what may happen one day.”

At 35, she already has a full life behind her. War, violence, loss, starting anew in a foreign country and becoming a mother; Fadia has taken everything in stride. Even more impressive is how she has managed to build a new life in the Netherlands from scratch and develop into a successful architect. “I still remember well how it felt when I arrived and couldn’t communicate with anyone,” says Fadia. “It was so frustrating. I wanted nothing more than to belong, so I mastered the language in record time. After that, things got a bit better.”

Integrating remembrance into daily life

Fadia understands first-hand how life and death go together. Currently pregnant with her second child, she also lost her mother not so long ago. Her father also is no longer with her. The impact of the Yemeni war and the loss of both her parents became the basis of her graduation research Moment van Herinnering (“Moments of Remembrance”). “Here, I tried to capture and analyse the spaces and the atmosphere that death has brought into my life,” says Fadia. She developed three imaginary places where someone can grieve, reminisce, and experience the grieving process. “In cities especially, there are barely any visible cemeteries. With my graduation research, I wanted to integrate the subject of death and remembrance into our daily lives more, but in less obvious places.”

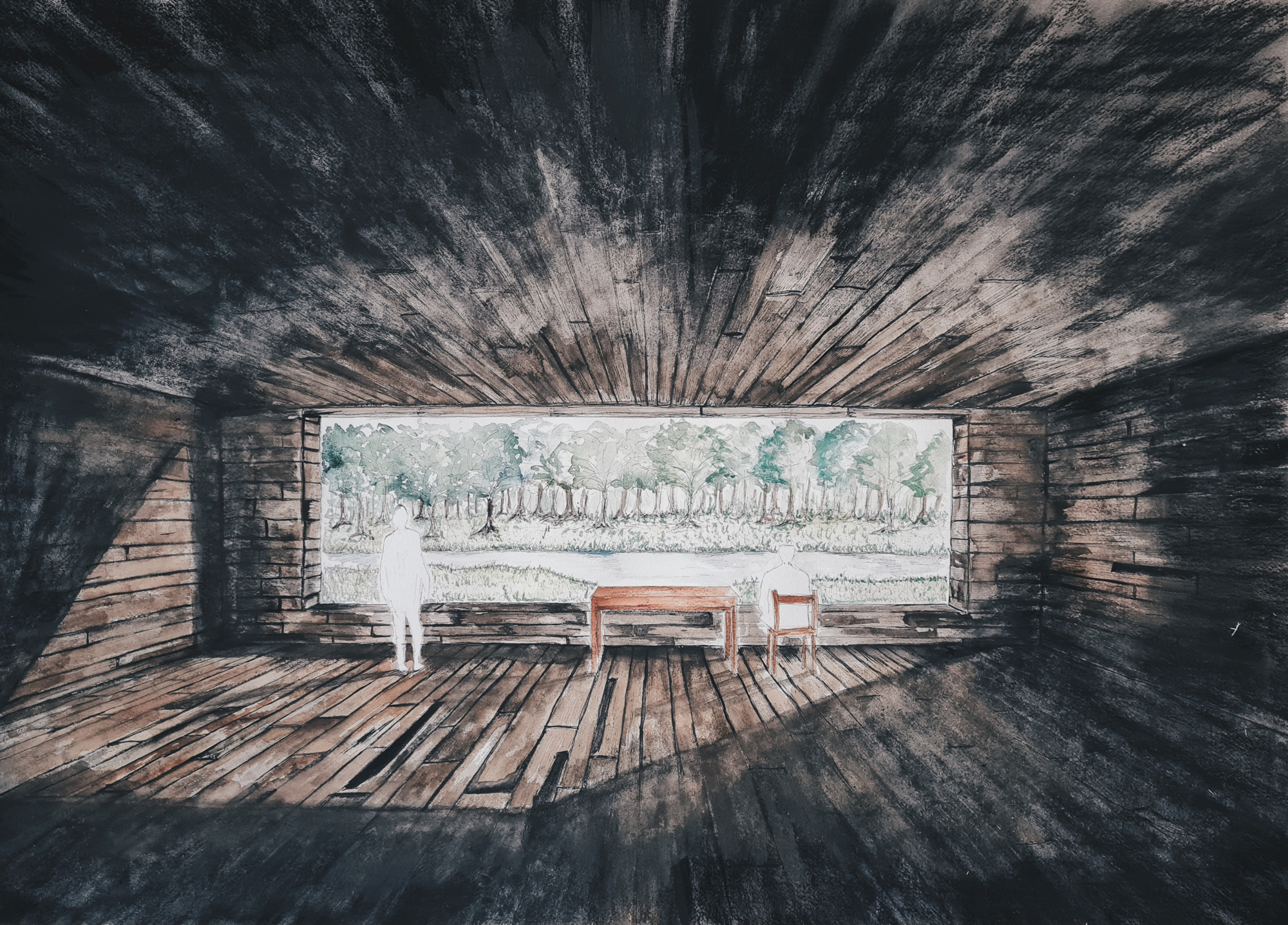

The dream as a place of remembrance – "There he sat, in his familiar chair, by the window, next to his table, surrounded by all his tools. There he sat, lost in deep thought."

A moment of quiet in the hustle and bustle of the city

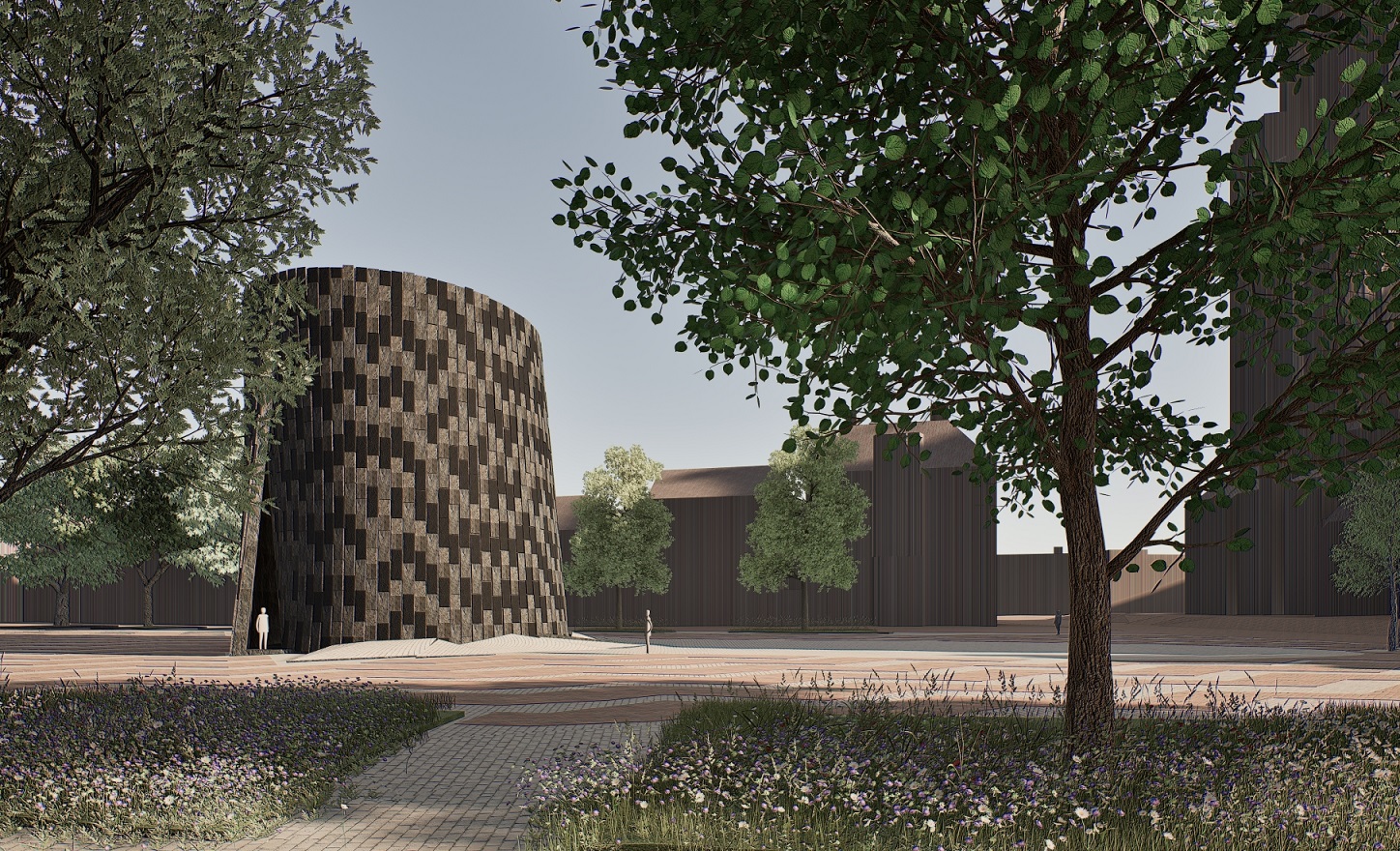

Fadia chose Arnhem as the prime location for her designs. Specifically, she focused her efforts on the Gele Rijders Plein, Ketelstraat and Markt. At the Gele Rijders Plein, she came up with a novel concept: a landscape with concrete tiles at various heights and thicknesses with mirrored, stainless-steel plates in between. “It’s playful, but it also confronts you,” describes Fadia. “It reflects life, where you have to overcome obstacles and sometimes get stuck or lost in the thick of it. Those are the same feelings you experience from the passing of a loved one. Despite that, this space also offers you a moment of peace. Amid the hustle and bustle of the city, you can pause here, slow down for a moment, and reflect.”

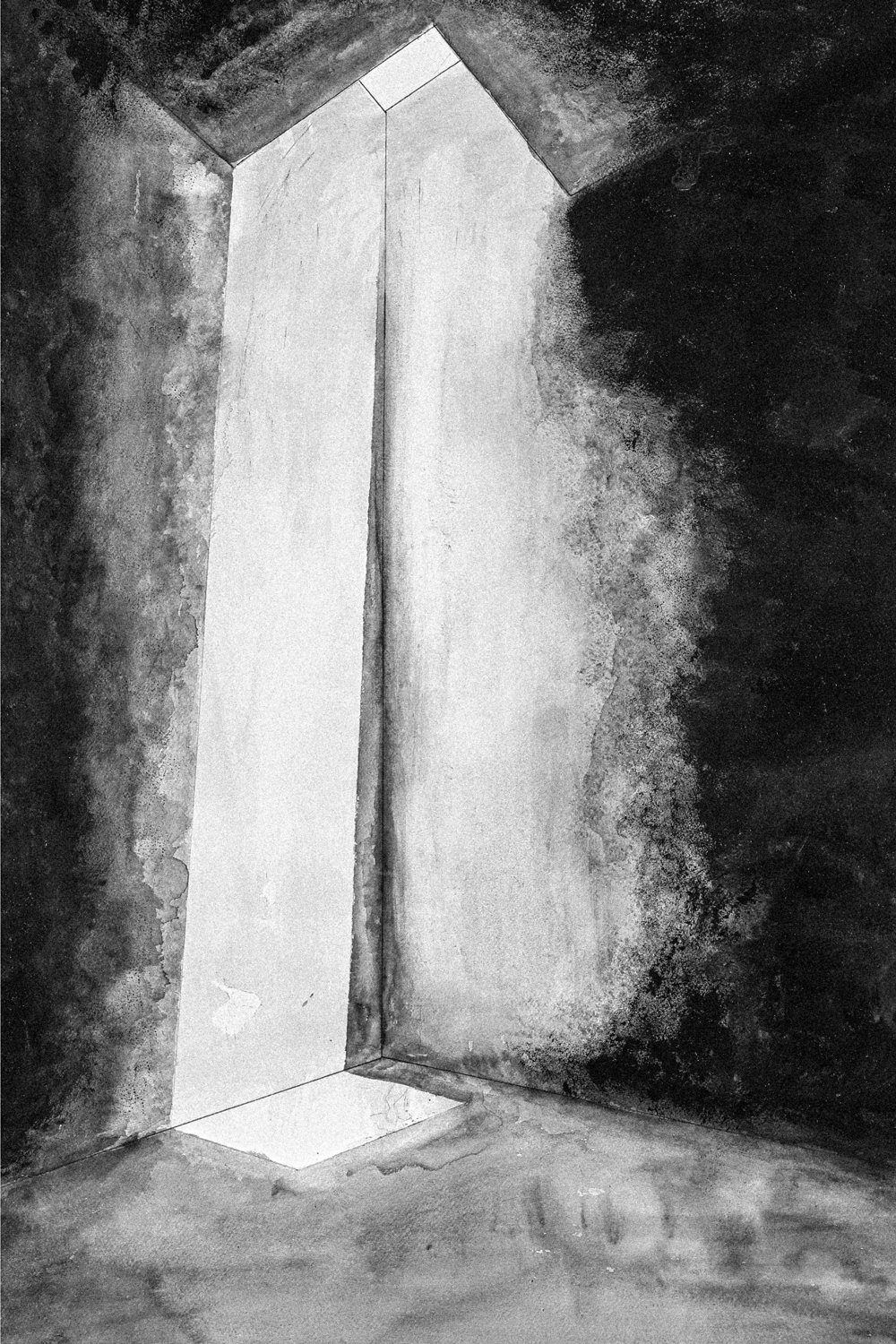

On Ketelstraat, her design used a part of a storefront where she wanted to create a contrast between the noisy motion outside and the anxious silence inside. In this design, she also emphasised height and depth. “The light shining above you was inspired by a place in Yemen where I often played as a child,” Fadia recalls. “That was where I went when I wanted to feel the rain. The hole on the floor was inspired by the empty wells I was always afraid of falling into. This combination of hope via the opening above and the anxious fear from the hole below evokes a wide range of emotions.”

Death is part of life

For the Markt, Fadia designed a mysterious object located partially above and partially below ground. Visitors enter via some dark stairs, which they follow down guided by a grid with water flowing underneath. As they continue walking, the walls grow smaller and smaller. Finally, they emerge in a light-filled space, fully enclosed by walls. You are stuck and cannot proceed further, with only an opening above you offering a sky view. Fadia: “This design symbolises vulnerability and the frantic search for a way out from difficult situations. It invites in reflection on moments of loss and hope.”

As to whether her graduation was a sort of therapy for her, Fadia says, “I thought it would be a good way to process my father’s passing. But halfway through my research, my mother also passed away and I questioned why I had even begun the research in the first place. However, I managed to complete it and do it well. Death is always a part of our lives. We must accept it, along with the pain it brings. Through everything that has happened, I am now no longer fearful of what may happen one day.”

Power in sharing her story

As a new graduate, Fadia is currently working at an architecture firm, but she is looking beyond the traditional frameworks of her profession. “Architecture is not only about designing chic villas, but above all about telling stories. I want to engage more in the future with social issues and help people through the medium of my designs. As to how, well, I’m going to explore that more in the upcoming years.” During events such as the Uitnacht in Arnhem (24 January 2025), she will share her vision by leading people on a walk past the places involved in her graduation research.

Reflecting on her time at ArtEZ, above all, Fadia feels grateful. “I met so many people from very different backgrounds,” she says. “As a student, you are also always receiving uplifting feedback that helps you develop and grow.” As to whether she has any tips for prospective Master Architecture students, Fadia says, “Stay true to yourself and choose subjects that speak to you. Your own stories are the most powerful ones. I used to be ashamed of the fact that I was from Yemen, a poor country without a notable architectural tradition. But now I’ve realised: The power lies precisely in those smaller, less beautiful things, because they are often much more interesting.”

Stories

-

"I know how terribly warm it is to be lugging things around on a building site in 30-degree heat, and how freezing it is at minus five."

-

Architecture master’s student Naomi: “Growing into what I am is more important than growing into what I ought to be”

-

Securing space to experiment with architects Jens Wind and Veerle Elshof